- Home

- Claude Salhani

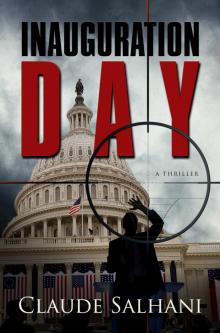

Inauguration Day Page 2

Inauguration Day Read online

Page 2

“Good question. Let us call him Omar. Yes, that sounds good. We shall call him Omar, after an Arab hero.”

“Omar it is.”

“Who else knows about him?” asked the sheik.

“No one but Kifah Kassar, the deputy commander in Lebanon, and of course the Doctor and his deputy, Zeid.”

“That’s fine,” said the sheik. “They are all trustworthy people.”

“Of course.”

“Anyone else?”

“Two others who assisted in the training.”

“See that they don’t talk,” said the sheik.

“Of course. You mean—”

“I mean nothing,” the sheik cut him off. “I leave it up to you to make sure there are no loose ends. Tell me more about Omar. His background, his experience, his skills. I take it he is clean. No dossier on him with any intelligence agency?”

“He is clean as a virgin on her wedding night. Depending on which story you choose to believe, our ‘Omar’ was born either in Iraq or in Lebanon. Some versions have him born in Afghanistan. I am not even sure that he knows for certain where he was born. I once heard him tell someone that he was born in Kuwait to Palestinian parents. He speaks all the local dialects and can easily pass for anything from Egyptian to Saudi, or Iraqi to Kurdish. He is excellent when it comes to picking up accents. He is like a parrot.”

“That is interesting,” interjected the sheik. “Do go on.”

“As I was saying,” said Abdelwahab, “he was probably born in Iraq to Palestinian parents. He lost both parents to a car bomb during the US invasion, when he was still in his early teens. He saw them die. He saw them burn and was unable to help them. Needless to say, that affected him greatly. One does not see such a scene without being marked for life. He blames the Americans for the death of his parents and is driven by his desire to take revenge. But what is interesting in his case is that he wants to do this in a calm and collected manner. People who are driven by a blind rage and want to see blood are dangerous to our organization and I, for one, tend to avoid them. Omar, on the other hand, is cool and calculated. He is a danger to his enemies and an asset to us.”

“I agree,” said the sheik. “That is an excellent assessment. Please continue.”

“Thank you. He was adopted, so to speak, by one of the local militias in Baghdad, the Doctor’s people. After the death of his parents he had nowhere else to go, no one to turn to. The Doctor’s people took him in and took care of him. These were very difficult times in Baghdad with much fighting everywhere. The lads chipped in whatever they could spare to buy him some clothes and shoes. The poor boy had lost everything. He started accompanying some of the fighters wherever they went, including, at times, into combat. His first tasks were simple ones: to carry ammunition to a team firing mortars on US forces in the Baghdad area; to carry messages back and forth when the boys did not want to use cell phones or two-way radios.

“One day he volunteered to accompany a two-man team sent out to fire mortars on a group of US Army troops who tried to move into a neighborhood under our control. The two fighters were killed by gunfire from a US Army helicopter that was flying overhead, providing cover fire for the troops on the ground below. Instead of running away, as he should have, as would be expected—as most people would have done—or at least seek temporary shelter until the helicopter flew away, he stood his ground, showing no fear. He pushed the dead fighters out of the way, as they had slumped over the mortar tube. He adjusted the mortar for height and fired his first mortar ever, and scored a direct hit on the American helicopter, downing it and killing all its occupants.”

“Quite a feat,” said the sheik.

“Indeed. Mortars are not typically used as anti-aircraft weapons. But he made it work. He then readjusted and fired off about ten rounds, one after another, picked up his tube and ran to safety before the first round even hit the ground. The rest of the mortars rained down like fire from hell and there was no way to stop them. The troops never knew what hit them, and they had nowhere to retaliate.”

“But then the Americans must have a file on him,” said the sheik.

“Irrelevant for our needs. Although he continued hitting US troops with accuracy, getting better every time, he was arrested in a raid on one of the safe houses when the Americans were looking for Abu Mussab al-Zarqawi. We knew he would never talk, even under pressure. Even under torture. His hatred of the Americans was so strong that it would override every other sentiment in his body. Because of his young age, the Americans thought he was the coffee boy. They never tied him to the mortar killings. They have a file of a young man whose name has since been reported as dead. As far as the Americans are concerned, the young lad they knew under a different name has long been dead.”

The sheik nodded in approval.

3

CAIRO, EGYPT

Chris Clayborne glanced casually around without really turning his head, allowing his eyes, protected by dark sunglasses, to glance from left to right and back. He did not want to make it look as though he was scanning the surroundings, checking to see if he was being followed, which he probably was, as most foreign journalists in Egypt were. Normally he could not care less, except this time he was specifically told by the man he had flown all the way from Washington, DC, to meet, to ensure he was not being followed.

Clayborne stopped outside a shoe store on busy Kasr el Nil Street, one of the major thoroughfares in the Egyptian capital. He took in the beehive activity of the Egyptian city, the largest in the Arab world, and the largest city in Africa, through the reflection of the store window. He was quite sure no one had followed him from the airport, but it was impossible to be sure. And he needed to be certain. He was quite certain that no single man or woman had followed him, but if there were numerous people on his tail, and they relayed themselves, it would be impossible to detect a tail. The reassuring factor was that when journalists were followed in Egypt, it was typically by the same tail, from arrival until departure. Clayborne knew that as a journalist, he was not high enough on the food chain of the intelligence services to merit more than one flunky to follow him and make note of whom he would meet, and then hand those notes in to a superior who would look at the list of names.

Names of government officials would be ignored. Members of the opposition or of the workers’ unions and syndicates, or Egyptian journalists known for being opposed to the regime, whose names were on the list would be summoned to the intelligence headquarters and asked—politely at first—to recount their interview. It rarely went further than that, unless the foreign journalist later published a story that portrayed the country or its leaders in a negative manner. Then the interviews at intelligence headquarters could get somewhat more unpleasant.

Still, the Middle East had taught Clayborne that one could never be too cautious. He had been to Cairo dozens of times in the past, and as far as he could tell, whenever he was followed, it had always been a single tail. His old instincts had suddenly returned as he stepped out of his hotel. And he was more curious than ever to learn why his old friend and one of his most trusted contacts, Walid Barakat, had suddenly called him in Washington and asked him to come meet him in Cairo. Clayborne had met Barakat nearly two decades earlier, in Beirut, back when they were both based in the Lebanese capital. At that time Clayborne was a young journalist, just starting out in the business, and the Palestinian had proved to be a good source. Make that a damn good source, thought Clayborne, someone who got him more than one exclusive story and helped propel his career in the right direction.

Clayborne knew right away that if Barakat asked him to fly to Cairo, it would be well worth the trip. He was not the sort of person who would exaggerate a situation to give himself greater importance. The hardest part was convincing his editor to let him fly five thousand miles from Washington, DC, based on a cryptic telephone call. And in business class, no less.

But it was, after all, such instincts that helped him survive and excel as a journalist in

the Middle East and to come up with the exclusive stories and the exclusive interviews. Now, at nearly forty, his senses for survival were stronger than ever.

Leaving the sanctuary of the Cairo Hilton, Clayborne ventured into the bustling city, pushing away a gaggle of street urchins eager to sell him faded postcards and a handful of fake souvenirs. The sun had begun to set, rendering the heat more bearable. A gentle breeze was beginning to blow in from the Nile, making this early September evening quite pleasant. Cairo metamorphosed at night. Once the crowds started to reemerge from their afternoon hibernation, the city would find its maddening pace once again.

Clayborne was glad to be back in the Middle East. The Cairo Peace Conference was finally going to take place in a few months. Even the recent spate of terrorist attacks against American embassies, followed by retaliatory raids by the US Air Force on suspected terrorist sites in Sudan and Afghanistan, was not going to deter the accords. Both the Palestinians and the Israelis were set on signing this historic peace treaty.

Yes, it felt good to be back. Washington, which he now called home, had become tedious. The abundance of political scandals had turned once serious journalists into nothing more than tabloid reporters. He hated that. This was a good time to go back on the road, to be in the field, covering a real story. It was also good to be away from Washington and the egocentric politicians and the media hordes that believed the world stopped rotating outside the Washington Beltway.

Soon after the war in Iraq, Clayborne was promoted to a desk job, given a big raise, and transferred to Washington. He never really adapted. He disliked Washington and home-office politics, and missed the Mideast and his friends. He had spent nearly two decades in the area, most of them chasing godforsaken conflicts that no one really seemed to care about, in places that most Americans couldn’t pronounce properly, let alone place on a map.

The afternoon air carried abundant sounds and smells of Cairo, mingling them with the throngs of people who darted between dilapidated automobiles, donkey carts, and overcrowded buses that seemed as though they would collapse at any given moment. Gray clouds of exhaust fumes drifted slowly above the streets, adding to the decades of grime that turned once virgin-white buildings into darker shades, ranging from dark gray to ebony black. Drivers leaned furiously on their horns, adding to the cacophony of shouts emanating from street vendors trying to lure customers for a final sale of the day.

Clayborne took in the atmosphere. Cairo was truly a city that never slept; it was unique in the Arab World. There were always crowds on the streets, no matter the time of day or night. Yes, he reflected, it was good to be back.

Only this time, he could feel the difference in the air. It was in the people’s eyes. Clayborne had learned to pick up these signs. It was almost a sixth sense. The eyes were different.

Clayborne knew the extremists could easily derail the talks. The recent bombings had accomplished nothing except create more hatred against the United States. American embassies from Rabat to Islamabad were on full alert and bomb threats had become a daily occurrence. And if one were to take the State Department’s warnings seriously, no American in his right mind should be traveling in the Middle East at this time. But no one in his right mind would travel to war zones for a living.

Clayborne reflected on the telephone call. What information did the Palestinian have that required Clayborne to come all the way here? Two days earlier, Barakat, now one of the principal advisers to the Palestinian president, got Clayborne on his office phone and said, “It would be nice to see you.”

That was his traditional code word. Barakat would never say something like “I have something important for you,” or “Come right away.” It was always something very low-key, such as, “It would be nice to see you.” Only this time, he added: “I have an item you might find a little interest in.” Then, after what seemed a little hesitation, “This has something to do with the bearded boys. I cannot say more on the telephone,” added Barakat, referring to the Islamists. Chris Clayborne knew the Palestinian well. If he asked Clayborne to make the trip, he knew it was big. Years ago it was Barakat that had gotten him inside a terrorist training camp. That was a real scoop!

Clayborne used a circular pedestrian crossing to traverse Tahrir Square, a large piazza in the center of the city near the Egyptian Museum. It would have been sheer madness to venture across the large avenues amid scores of buses and hordes of taxis. There seemed to be absolutely no logic in the traffic pattern. Clayborne walked casually towards Kasr el Nil Street to Filfila, a small restaurant that served foul and falafel. He entered from the front of the restaurant, made his way to the back, and went out the back door. No one followed him. He continued for another block until he reached Groppi. It was a pleasant walk that took him about ten minutes. At the once fancy tearoom, Clayborne selected a table in the back of the café, close to the wall, but that faced the entrance. He ordered Turkish coffee.

The man Clayborne knew as Walid Barakat arrived ten minutes later. The Palestinian looked much older than his forty-seven years. His hair, or the little that was left of it, had turned white, and the once svelte guerrilla fighter had put on an additional thirty pounds around his waist. Walid greeted Clayborne with a kiss on both cheeks and a firm handshake. “My dear Chris, it is so good to see you again. How is Washington?”

“Quite boring, I am afraid, my dear Walid, quite boring,” re-plied Clayborne. “Far too many money scandals involving members of Congress, right-wing lunatics pushing for war against any country that objects to US hegemony in the greater Middle East, and crazy Republicans bent on proving the president is not really an American. Meanwhile the Democrats are going all-out, behaving worse than the Republicans to prove that they are just as red, white, and blue as the other guys.”

“Ahh, I suppose one cannot have it all,” replied Barakat, with a loud laugh. “My dear Chris, you are beginning to sound like an angry Arab. There may yet be hope for your salvation.”

“And how is Gaza?” asked Clayborne. “I see you are well.” He gestured towards the Palestinian’s waistline.

“Oh, Gaza is still the armpit of the world,” said Barakat. “We have no sex scandals to speak of, since our friends with beards have decreed that women should be veiled, even on the beach. We have no money scandals, because basically we have no money,” added the Palestinian, with a loud laugh.

“So why are you staying in Gaza?” asked Chris. “Why don’t you move to the West Bank? Ramallah or Jericho? Or even Jerusalem?”

“The president wants me in Gaza,” replied Barakat. “I have an excellent network of informers and agents working for me. And today, learning what the boys with beards are concocting is far more important to us than spying on the Jews. Listen, Chris, I don’t have much time as I must get back to the president, so let me get quickly to the point.” Clayborne nodded and took a sip of his sweet Turkish coffee.

“The president knows fully well that only peace will bring prosperity to the Middle East. His predecessor missed a golden opportunity to have a Palestinian state declared and recognized. Even if it would have been far from perfect, it would have given us a state to call our own. This president is sick, he is dying, he knows it, and he wants to be remembered as a peacemaker. He wants it to succeed. Call it his legacy to his people. He wants to lead them out of their political wilderness.”

Walid lit a cigarette, took a long puff and looked around to make sure no one was close enough to hear him before he continued. “Chris, this is completely off the record. I never said any of what I am about to say. Feel free afterward to do what you want with it, but we suspect Doctor Hawali and our dear friend Sheik al-Haq to be in possession of biological agents and they may be planning an attack on the US.”

“So the raid on Khartoum was justified?”

Walid smiled and nodded his head. “We believe so. We know that Hawali and those opposed to the peace process will want to strike and abort the conference. And our information indicates this will happen s

ooner rather than later. Certainly before the conference starts. They want to derail it.”

“How solid is your information?”

“Solid.”

“Can you share the source?”

“You know better than that. But you heard about the killing of the American agent in Beirut last week? We know it is related to that.”

“So why are you telling me this?” asked Clayborne.

“We want to save the peace talks, yet we cannot go public. We want the world to know, public opinion to know, that we want peace. We have had enough war and enough fighting. I have with me photographs, photographs which I will give you, that prove the Sudan plant was hot.”

“And as usual, these come from ‘unnamed sources.’ Right?”

“Right. You found these on your doorstep.”

“I’ll have to check with other sources.”

“Officially, we cannot confirm or deny. But Chris, the entire peace treaty is in jeopardy. We are afraid these actions by the extremists will set us back thirty years, maybe forty years if not more, and will bring more bloodshed to the region.”

“Why don’t you go directly to the Americans with this information?” asked Chris. “You have high-up contacts at Langley.”

“Yes, of course I do, but there is also a mole in Langley working for the bearded boys. I have double-checked. There is an insider at Langley passing everything we have to the Islamists.”

“What can I do?” asked Clayborne.

“Expose the story, but don’t expose me. If you do it, if you expose them, if you publish this information, you will upset their plans. They can no longer continue and risk being exposed. But please be careful, my friend, be very careful of who you trust. One more thing—while we don’t know where or how, we do know the date on which they plan to strike. Next January 20.”

“January 20? You sure you got that date right?”

“Why, what’s so special about January 20?” asked the Palestinian.

Inauguration Day

Inauguration Day