- Home

- Claude Salhani

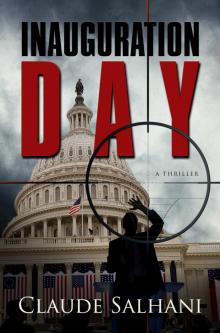

Inauguration Day

Inauguration Day Read online

Other works by Claude Salhani

Islam Without a Veil: Kazakhstan’s Path of Moderation

While the Arab World Slept:

The Impact of the Bush Years on the Middle East

Black September to Desert Storm:

A Journalist in the Middle East

Copyright © 2015 by Claude Salhani

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Yucca Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Yucca Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Yucca Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or [email protected].

Yucca Publishing® is an imprint of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.®, a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.yuccapub.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover design by Slobodan Cedic for Yucca Publishing

Cover photo credit: Courtesy of the National Archives

Print ISBN: 978-1-63158-063-5

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-63158-076-5

Printed in the United States of America

For my children, Justin and Isabelle

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A very hearty thank you goes to two people who each in their own way offered tremendous help: Stephanie Thompson and Micha Tanios.

1

BEIRUT, LEBANON

Paul Hines was very nervous. This was somewhat unusual for a man who was known for being calm and collected. Those who knew him well knew he was not a man who would panic easily, even under the most strenuous circumstances, even under fire, something Paul Hines had experienced more than few times in his long and distinguished career. Paul Hines was what some people called a spook. He was, simply, a spy for the Central Intelligence Agency. Yes, they still have those, except that few people knew what he really did for a living. To many people’s knowledge, Hines was employed by the US embassy. He was a commercial attaché; one of many, although he was under no illusion the people who needed to know, knew what his real job at the embassy was all about.

Hines had been a spy most of his adult life. He was good at it and he liked what he did. He believed in what he did. But at the same time he was also a realist. Times had changed. The Company had changed. Things are not as clearly cut as they were in the past. His mind drifted back for a moment to the days of the Cold War when life seemed so much simpler. At least then we knew who the enemy was, Hines reflected for a brief instant. Today the lines were often blurred. Sometimes the good guys were behaving like the bad guys. Hines knew his Company had done many things one could not be proud of, especially in the past decade, but it was a nasty world out there. And hey, the bad guys were doing far worse things. When dealing with bad guys, you need to be as ruthless as they were if you were to get results.

Now nearing retirement age, whenever he got himself into a tight spot he began to feel as though he had used up his quota of good luck. As the years went by, the more he found himself in tricky situations and the more he thought he might never make it back to the United States alive. Those who did not know him well were surprised to learn his age: sixty years and climbing. He still had a full head of hair; it was graying, but still there. He kept himself in top physical shape through a rigorous morning exercise regimen that many much younger men could not keep up with.

Hines was an optimist by nature. He was not one to look on the dark side of things, always taking an optimistic approach to a situation, regardless of how dark the cloud’s lining might be. Paul Hines always managed to extract something positive from any task he handled and his positive attitude seemed to rub off on those he worked with. Those who knew him well also said that you needed to have that kind of attitude if you were doing the kind of job Paul was doing, and living in a place like where he was living. As the CIA Beirut station chief, working out of the US embassy in Lebanon, he knew there must have been a long list of those who wanted him dead. Indeed, his job was not something anyone could do. It required nerves of steel, especially in a place like Beirut, where there were no secrets—and Paul Hines had them. Officially he was accredited as a commercial attaché, and other than the ambassador and his deputy chief of mission, no one else was supposed to know his real function. But everyone did. Though they pretended not to. Hines was often invited to dinner parties hosted by Beirut’s elite, where some of the women tried to seduce him so that they could later brag to their girlfriends that they had slept with a real CIA spy. With one or two exceptions, Hines avoided them.

It was the same on the Lebanese side; only the head of the country’s internal counterintelligence services and the head of the military’s Deuxième Bureau were supposed to know of his real functions at the embassy, but Hines was certain that minutes after his arrival in Lebanon, all concerned intelligence agencies, from the Lebanese militias such as Hezbollah to the Syrians and Palestinians and Iranians, had a dossier on him. But that was part of the job and he accepted the risks.

Yet try as he did, there was absolutely nothing positive to be drawn from the frantic telephone call he had just received from his top informant in the country. Something today just didn’t feel right. After years of staying one step ahead of those who wanted him dead, and often tried to kill him, he had developed a certain sixth sense. Common sense told him to stay away from this hastily-called-for meeting requested by the informant. It had all the markings of a trap. But Paul Hines also knew that the information his informant had obtained was most likely vital, or he would never have made the call. After having worked in the field as long as Hines had, sniffing out danger became second nature.

His intuition was right, because the intelligence his informant had inadvertently stumbled upon was worth more than his weight in enriched uranium. Hines was soon going to learn that his agent had inadvertently stumbled on a plot to assassinate the president of the United States. It had happened in the most unexpected manner. One would assume that people in the business of assassinating the president of the United States would have taken a few more precautionary measures, such as making sure the room was clear before sitting down to discuss such issues. But that was a lucky break for “the good guys,” as Hines would say.

Hines did not know of that plot yet, but he felt that whatever his informant would tell him in a short while had to be huge. He was, however, right to worry about today, because he also did not know that he would be dead in less than three hours. His death would put an end to a brilliant career with the Central Intelligence Agency, one spanning forty years and more than fifty countries. Hines had been responsible for bringing down at least six governments—three in Africa and three in the Middle East—but few people knew that and it was not something he wanted to brag about. It was just part of the secretive nature of his work. Some things were better left in the dark.

The short and frantic telephone call from his most valuable source in Beirut left him wondering why his contact broke all the security protocols by speaking on an open telephone line. Hines ran the conversation back through his mind over and over. It was short, and lasted just a few seconds, but long enough to tell there was fear in the informant’s voice. Genuine fear. That much he could tell.

The fear he heard coming from his informant over the telephone line was not prompted or faked. That meant there were three possibilities: one, the contact was in imminent danger an

d had to get the information to him before the person or persons following him got to him first. The informant must have been followed, otherwise he could have made a run for the US embassy in the hills above Beirut and sought refuge there, seeing his cover was blown anyway. If he phoned rather than drove to the embassy, that meant he was unable to shake his tail, or they could be waiting for him.

Two: The contact was already in the custody of whoever had him and forced him to make the call in order to get to Hines. But if that was the case, why did the informant not use the agreed-upon code word indicating he had been compromised and was acting under duress? It was a simple code word that no one would catch other than those looking out for it. The contact didn’t use it, so this reinforced the first theory.

Three: The contact had been turned by his intended target and was setting him up for a trap. That was unlikely, given his background. Either way, it did not look good.

Hines chose to focus on the first theory: that the agent was running for his life after stumbling onto something he was not meant to have heard or seen. Whatever it was, it did not look very encouraging. Paul Hines tried to reassure himself that he had been in tight spots before. But try as he may, Hines was unable to shake that nasty feeling; that gut feeling that something would go terribly wrong before the day was over.

2

CAIRO, EGYPT

His eyes closed, Sheik Hamzi al-Haq waved his hands in a gentle motion over his face as he finished reciting the evening prayers. The old sheik remained in a sitting position, resting his aching body on his folded legs and lowering his hands into his lap. Years spent in an Egyptian prison with regular beatings kept him in nearly constant pain. He opened his eyes and stared at his palms for several long minutes. Every now and then, he stroked the long, gray hairs of his beard, as if the motion offered him some inner strength. The decision the sheik had just reached had not been an easy one. The old Egyptian had been agonizing over it for days now, hoping that somewhere there would be an answer. But there wasn’t. The new weapon was finally delivered and ready to use. Even the American raid would not stop them now.

Sheik al-Haq opened his eyes and felt around for his thick eyeglasses; he was practically blind without them. In the distance, a call to prayer went out from a muezzin and was echoed by several other mosques, each a second or two apart. The sheik listened to the familiar sounds; they somewhat soothed him. He picked up his glasses and put them on. The small, bare room slowly came into focus. The sheik found a microphone that was attached to a small battery-operated tape recorder and turned the switch to the “on” position.

“In the name of God the merciful and the almighty. In the course of his lifetime, man is forced to face a multitude of avenues and to choose the one that will take him to the gates of redemption and to the Kingdom of Allah. Other roads, those of temptation, will result in a direct path to eternal damnation and a life with the devil. It remains man’s responsibility to identify the right road to follow and remain true to the teaching of our faith and our prophet, peace be upon him.”

The sheik continued recording for another twenty minutes; his voice—already broken by repeated prison terms, beatings, and torture—sounded even weaker, thanks to the inexpensive recording equipment being used. Yet there was a certain serenity about his voice, something reassuring. Perhaps it was the calmness he projected, the deep thought, the self-assurance with which the sheik continued speaking for about twenty minutes, after which he turned off the tape recorder and removed the cassette. He raised himself and walked to the door, where one of his bodyguards was waiting outside.

“They are waiting for you downstairs,” said the aide, taking the sheik’s arm and gently guiding him down the long, narrow staircase.

“Let us go then,” replied the sheik, handing the cassette to the aide. Like others before it, the cassette would be copied and tens of thousands would be distributed at mosques around the country, to disciples of the sheik, following the Friday prayers. Some would find their way to believers as far away as Afghanistan, Pakistan, and even Indonesia. There were faithful people ready to follow the sheik all over the world.

On the lower level of the two-story building in a working-class neighborhood of Cairo, a group of five men had been waiting for the sheik. The men sat around a small coffee table on two red velvet sofas covered with cheap thick plastic to protect and prolong the life of the cheap imitation velvet. The summer heat made sitting on the plastic uncomfortable. The room was shuttered and there was no air conditioning. But it wasn’t the heat that preoccupied these men.

One of them reached over on the coffee table and took a cigarette from one of the many packets lying on a large round dish that was meant to hold fruit. He took a lighter from his pocket and lit his cigarette. Two of the other men were also smoking and the blue smoke lingered in the room like a morning fog.

The five men rose in unison when the aging sheik entered the room and greeted him warmly. “Assalamu alaikum,” they intoned, wishing peace on their leader.

“Wa alaikum assalaam wa rahmatullah,” replied the sheik, motioning the men to sit down. The sheik chose the armchair between the two sofas and sat himself down. “The time has come to act and we must do so at once,” said the sheik, looking at the five men in front of him. “For the sake of the Arab nation, we cannot allow the Americans to go unpunished. We cannot allow the traitors to sign the treaty. We must act quickly or we will be sidelined and our movement will become irrelevant.”

“We are ready now, your holiness,” said Abdelwahab, the man in the wrinkled gray suit. He opened his briefcase and took out a small black metal box. He placed the box with great care in the center of the table. The man opened the box to reveal a metal tube, slightly larger than a cigar. The tube was resting in a bed of foam and cotton. “Here it is, your holiness,” said Abdelwahab. “We got this out of Sudan before the American attack.”

The sheik stared at the small metal vial for almost an entire minute without speaking. Although the contents of the vial were not visible to the men in the room, it was as though there was some mysterious force emanating from the container. It was almost as though the vial contained some magic, or some supernatural force that could transform the lives of those in the room.

“How powerful are the contents of this container?” the sheik finally asked.

“Enough to eliminate five city blocks, your holiness. This is only the first batch. Unfortunately, we lost the Khartoum facility last week. That set us back a while. We were only able to produce the little we have here. However, we do expect Kabul to become operational within two or three months at most, if all goes well.”

“What about the Americans?” asked the sheik.

“They suspect nothing,” replied the man whom the sheik knew as Abdelwahab. “What we have done, your holiness,” continued the man in the gray suit as he adjusted his thick glasses on his nose, “is still experimental, but it worked fine in our laboratory. To obtain the results we need, and be able to smuggle the weapons in adequate quantities, we had to find a more powerful ingredient.” The man paused to see if the sheik was following his explanation.

“Go on,” said the sheik.

“It is relatively simple, for the scientists, that is. And that is largely thanks to the training they received in American institutions of higher education.” The man paused to let the irony sink in. “What we have done is combine two very lethal toxins, Bacillus anthracis, otherwise known as anthrax, and VX. The new combination is about a hundred times more powerful than either of the two other compounds.” The Egyptian took another cigarette from the tray, lit it, and continued. “To give you an idea, one pound of anthrax alone has the power to kill everyone in an area as large as Manhattan, while a single drop of VX the size of a pinhead is also lethal. This new combination is even more powerful. When this new toxin is released into the air and absorbed through the lungs or skin, it inhibits the release of acetylcholine at neuromuscular junctions.”

The others, in

cluding the sheik, gave him a puzzled look.

“In other words,” said the man known as Abdelwahab, a scientist who had received his degree in Great Britain, “it leads to instant paralysis. The lethal dosage is only 0.02 milligrams per ten seconds, per ten cubic meters. That is very powerful. You see, ordinary botulinal toxins take about six to eight hours to take effect. This combination works within seconds, minutes at the most. The symptoms are combined. Instant dizziness, sore throat, dry mouth, excessive weakness of the muscles, paralysis, bleeding from the nose, mouth, ears, and eyes. There is only one downside to the new compound.”

“Go on,” said the sheik.

“In order to stabilize this new mixture, we had to add yet a third compound.” The man looked at the sheik, as if waiting for his prompt.

“Continue,” said the sheik.

“Unlike ordinary anthrax, if this compound comes into contact with water, the effect is greatly reduced and might even lose its lethal edge. But we don’t expect to drop this in a body of water and thus we have to transport lesser quantities. Lesser quantities to transport means less chance of being stopped at a border.”

“Fine,” said the sheik. “We must strike right away.”

“We are ready,” said one of the other men. “Our Iranian friends will deliver this vial to our man in Washington when we get closer to the operation window.”

“So be it,” replied the sheik. “Let it happen, then. We must make sure the peace process does not go through! Have you identified the right person for the job?”

“Yes, your holiness, we have. His name is—”

“Don’t tell me his name,” interjected the sheik. “I don’t need to know it. Don’t tell anyone his name. They don’t need to know it either. The fewer people who know, the fewer chances of information leaking out.”

“Granted, but how do you want to refer to him?”

Inauguration Day

Inauguration Day